Available Now on Amazon

Don’t Bet On It is the tale of a 28-year love story – one delicately shadowed and eventually ended by the presence of death. Even more, this is the story of a slumber party, therapy session and private joke, all wrapped into one. It’s a portrait of intimacy, of a man and a woman who lived for the chance to connect, all the while aware of the potentially fatal effects of a deadly illness called lupus.

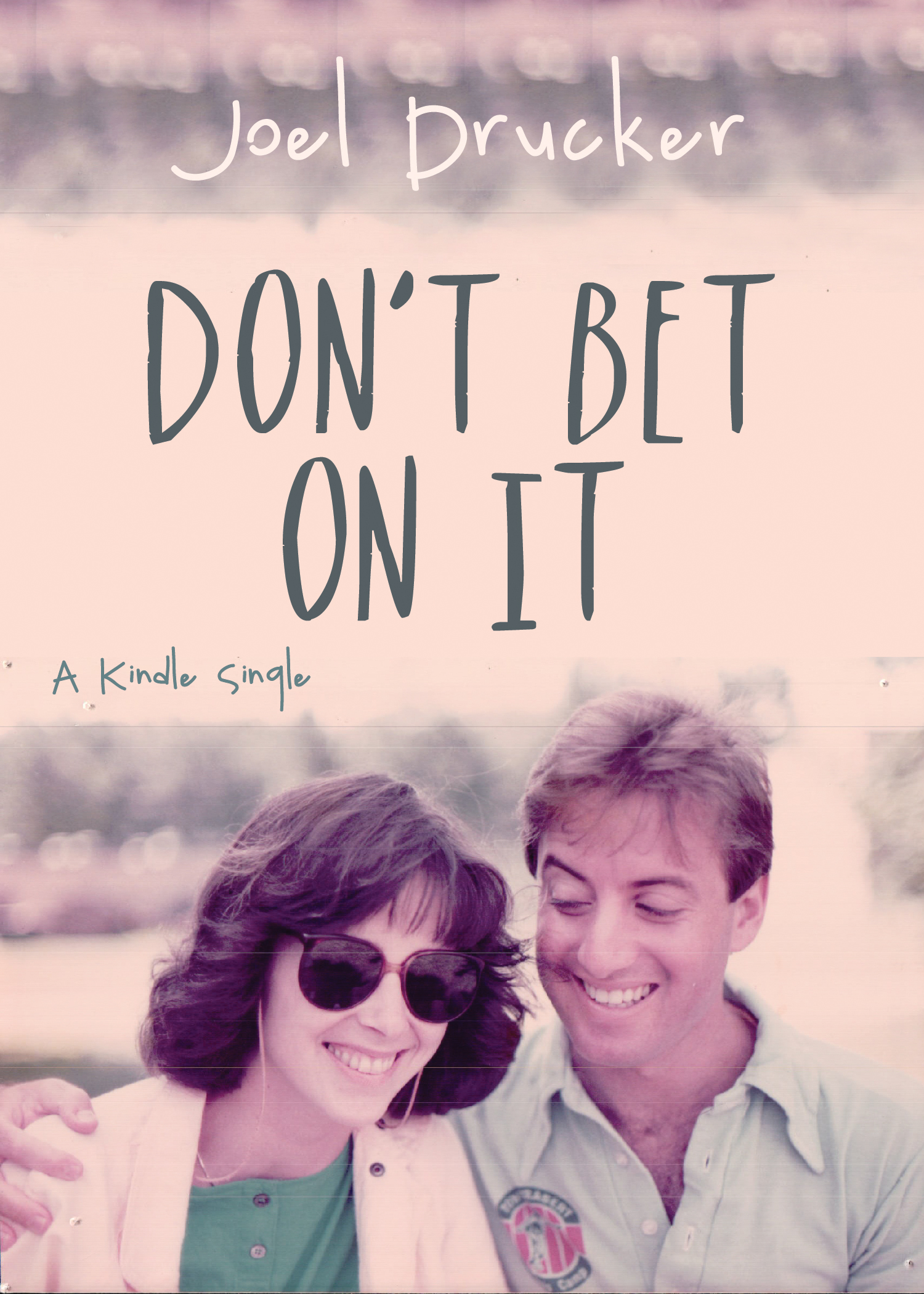

Joan Edwards and Joel Drucker met when they worked together in the summer of 1982 for Inside Tennis, a magazine based in Oakland, California. Joan was the art director. Joel was the managing editor. They’d met in May. Their romance commenced in August. In 2010, nearly 28 years to the day of their first kiss, Joan died.

The DNA that connected these two, formed even before they met: humor. As the book explains, the two met through humor, which even from the start, was twined with death. Don’t Bet On It draws on examples of the way humor worked as a way to escape, confront and connect – everything from a book of jokes Joan kept near at hand for nearly 50 years, to a heartfelt quip about Apollo 11, to a sardonic connection between Joan’s health and “The Godfather.” Even the very title, Don’t Bet On It, has its roots in a crack Joan made to Joel on his 29th birthday – a prophecy that indeed became true.

This is Joel Drucker’s second book. In many ways, the approach is similar to his first. That book, titled Jimmy Connors Saved My Life, was a portrait of an iconic tennis star who dramatically shaped the direction and texture of Drucker’s life. Woven into that book were Joel’s painful experiences watching his older brother be inflicted with schizophrenia and the sudden death of his father.

In Don’t Bet On It, Drucker explores the nuances of life and love with his soul mate. One year before the two met, Joan had lost her father (her mother had died when Joan was 16) and been diagnosed with lupus. How did Joan’s precocious sense of mortality shape the path of their love? Why did faith prove more important than confidence in this romance? What was gained? And what, in the end, was lost? As the book nears its close, Drucker describes the last week of Joan’s life with agony and precision: “The nurse tells us the end could come in five days or three weeks. Which is better?”

If you reason, quite understandably, that a memoir that begins with the imminence of death is too sad, allow Joel Drucker to surprise you with this invitation to remember the laughter and the intimacy, the quotidian ecstasy, the joy and pain of human connection – a love complicated by illness, but never defined by it. Don’t Bet On It will break your heart in places – and put it back together in others. Readers will see the world in a different way. This truly is a tale of love and death.

Early Praise

“Joel’s story of Joan is a beautiful and passionate tale of two first-rate competitors who fought hard for their love.”

–Billie Jean King, Social Justice Pioneer and Sports Icon

“An unflinching, moving and poetic memoir that reminds us not only do memories keep us alive, to truly honor them we must keep living. And we must not forget anything.”

– Alex Green, Author of The Heart Goes Boom

“A meditation on the primacy of hope. The horrors of illness and mortality may weigh on us, Drucker declares in this lovingly told tale, but the heart, in the end, outweighs them all.”

– Shobha Rao, author of An Unrestored Woman

“Joel Drucker’s introspective look back at the life—and death—of his wife, Joan, was both absorbing and poignant. This story is a timely reminder of being there ‘in sickness and in health’ for your spouse.”

– Mike Yorkey, author or co-author of more than 100 books and co-author of Holding Serve by tennis star Michael Chang

“This is a love story and also what I’d call a life story: two people meet when they are very young, fall in love, and stay together for 28 happy years, when death, prematurely and cruelly, doth them part. Joel Drucker writes with an effortless fluency and sensitivity about his beloved wife Joan’s long, brave confrontation with lupus, and his steadfast love and support for her during this long illness. This is a supremely tender and beautiful memoir–graceful, witty, and ultimately devastating.”

– Christine Sneed, author of The Virginity of Famous Men and Little Known Facts

“Through love, kindness and humor, ‘Don’t Bet on It’ offers inspiration to everyone with lupus and autoimmune arthritis who want nothing more than to live their lives to the fullest, not let their disease define them and, hopefully along the way, find the once-in-a-lifetime love that is the story of Joan and Joel.”

– Helene Belisle, Executive Director, Arthritis National Research Foundation

A Conversation with Joel Drucker

- You write about “stealing the structure of The Great Gatsby” to write Jimmy Connors Saved My Life. Is there a comparable literary structure in your memoir about your life with Joan?

When Joan and I were alive, pretty much from the start of our romance, we cast our story as an epic tale, one we knew had started before we’d met, complete with personal details, significant songs, geographic proximity and emotional connection. And that continued during our time together, as we pondered various years, themes, events, trips and so on.

But after she died, everything split into fragments. Memories hit me randomly, like a kaleidoscope or collage – varied, singular and un-sequenced experiences, constantly cutting back and across time. In the weeks after Joan’s death, I’d look at the personalized greeting cards she’d made for me, listen to the songs we’d taken delight in, hold pictures in my hands, pondered the many movies we’d watched together, reread the notebooks I’d kept the last summer of her life – and it all kept hitting me as a series of snapshots, vignettes, moments. Click. Click. Click. Click at the supermarket we’d shop at. Click at the pizza place. Click driving past a doctor’s office. I wanted to write something more intimate, personal, delicate. Earlier drafts had far more flashbacks. In time I found a structure that was both somewhat linear-accessible and staccato.

As far as influences go, I’ve been stealing from Joan Didion since I was a teenager. Didion’s precision, candor and capacity for understatement, telling details and pointed generalizations has always appealed to me. So naturally, The Year of Magical Thinking, the tale of her husband’s death, was an initial inspiration, a book I reread within a week of Joan’s death. But in time I saw that Didion was too emotionally frugal for my tastes. Where was the joy in her marriage? So while Didion’s craftsmanship mattered to me, I sought something far more emotional.

- There are many memoirs about marriage and dying. How do you describe Don’t Bet On It in casual conversation?

Immediately after Joan’s death, I read many mortality memoirs. Just after I’d finished reading A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis’ reflections on his late wife’s death, a joke construct Joan and I often employed came to mind. C.S. Lewis: too remote and ethereal. But what about Chicken Soup for the Grieving Soul? Not remote and ethereal enough. The likes of Didion, Lewis and other literary types hit me too much in the cognitive realm, as if I was reading them for a Tuesday afternoon English class. Their pieces were observed, as if each survivor was more witness than participant to love and death. But the ones like Chicken Soup were too vocational, generic, obvious. I remember seeing one book aimed at men who’d lost their wives with a toolbox on the cover, as if addressing grief was a mechanical problem that could be solved by deploying proper tools. Not a good gestalt for a liberal arts guy like me.

So instead, seeking to wedge into its own place, Don’t Bet On It was meant to be at once intimate, personal, idiosyncratic (like our marriage). Most of all, I’d call it a portrait — of our marriage, humor, lupus and the last week of Joan’s life. Once upon a time, as a history major and aspiring biographer, I was drawn to the epic sweeping canvas. But I’ve come to see lately that I’m more disposed to the small but revealing snapshot. That was in large part the way Joan and I were. After all, as the book describes, our wedding had no guests, no big party, no registering – none of that. Just the two of us.

- There is a touching scene about traveling from California to Joan’s home in Michigan shortly after your father died. She turns to comfort you in your fresh grief, saying that your dad’s time had come and that “you’ll always have me.” In the days and weeks after Joan died, who did you turn to and who showed up for you? Any surprises?

Those first few weeks it was like a football scouting combine. Everyone turned out for the tryouts – cards, dinners, phone calls. But as I was warned, in due time, people of course got on with their lives and I was left with the varsity. It was very nice to see how many people from the international tennis community rallied to my support, ranging from notes and phone calls to various expressions of support. As an individual sport, tennis doesn’t always lend itself to team play, and I too have typically been a rather self-reliant kind of loner. So to find that there was indeed a community of people in my corner was remarkable – and I continue to draw on it.

There were others locally who supported me too. It was rather random, but yes, many were quite kind, including a number of my tennis friends.

But I also saw how some people I’d known for years just didn’t have the stomach to be around my massive wound. It was clear, for example, that one longstanding friend of mine was too toxic and I haven’t spoken to him since shortly after Joan’s death. Another friend spoke to me at length about how I might want to sue Joan’s doctors for medical malpractice. Oy. The biggest surprise came when I heard from a woman I’d known as a teenager and hadn’t spoken to since 1981. Seven weeks after Joan’s death, we had a phone conversation that lasted five hours – and we’re now extremely close. I’d count her as one of my dearest friends.

But a year after Joan’s death I realized I needed more local community, more people who were literally near me. A lot of that was trial and error, including some rather frustrating interactions with people I thought I could get close to but in the end it didn’t quite work that way. But during this time, I met someone who was really willing to listen and take in my journey – the first significant friend I’d made after Joan. She remains an incredible source of support.

- Is there truth to the rumor that Emily Dickinson died of lupus? Why do you think it was important for you to find not just a famous person but a famous literary person who died of lupus?

Born in New York, raised in LA, educated at Berkeley, the child of parents who loved movies, theatre, politics and writers, I see indeed how I’ve always been drawn to and sought public recognition – OK, yes, fame. It did indeed mean something to me when Joan told me that the writer Flannery O’Connor had lupus. At one point I applied my liberal arts skills to reading her work and seeking signs of lupus. Joan kindly took me to task for that, “If you want to try to understand me by reading about a famous person with lupus, go ahead. But maybe you’ll have a better chance of understanding me if you just try to understand me.”

As far as Emily Dickinson goes, Joan said that to me in passing soon after we’d first met. But we never read much of her while together. But then, after Joan died, I explored some of Dickinson’s work and found myself intrigued by her mix of mortality and humor – two of Joan’s most notable qualities.

- Was there something funny or otherwise amusing that someone said or did with a mind for being supportive that actually was not?

A week after Joan’s death, I was riding an exercise bike at my tennis club. Alongside me was another member. He’d been out of town for a little while, and asked me what was new. When I told him, his reply was, “I can relate to your loss. Last week I lost in the first round of a tournament.” It took me about a year before I could talk to this person again.

Joan had always been attuned to the way people evaded pain. “They say they don’t want to ask about my health because it might make me feel uncomfortable,” she’d say. “But it’s not me they’re worried about. It’s them.” Eventually I came to see it this way: Life is a potluck. Everyone brings what they can.

- You write about Joan “jumping up and down in excitement” when, in 2003, you told her that your first book proposal had been accepted. Given that you submitted Don’t Bet On It to 45 different agents, all of whom passed on it, what might Joan think about your decision to publish this book with Amazon?

As she did with the first book, she would say that the most important thing was that I wrote the book. Then she’d tell me that while I’d like to see those agents all jump in the lake, it would be better to bypass any vindictive feelings and be glad I’d found home.

- Was it hard to mix illness, loss and humor? This book at times is quite funny.

It wasn’t hard at all – because it’s precisely what we had. One of Joan’s favorite lines: “It’s funny because it’s true.”

Follow the #hashtag #don’tbetonit across Twitter and Facebook